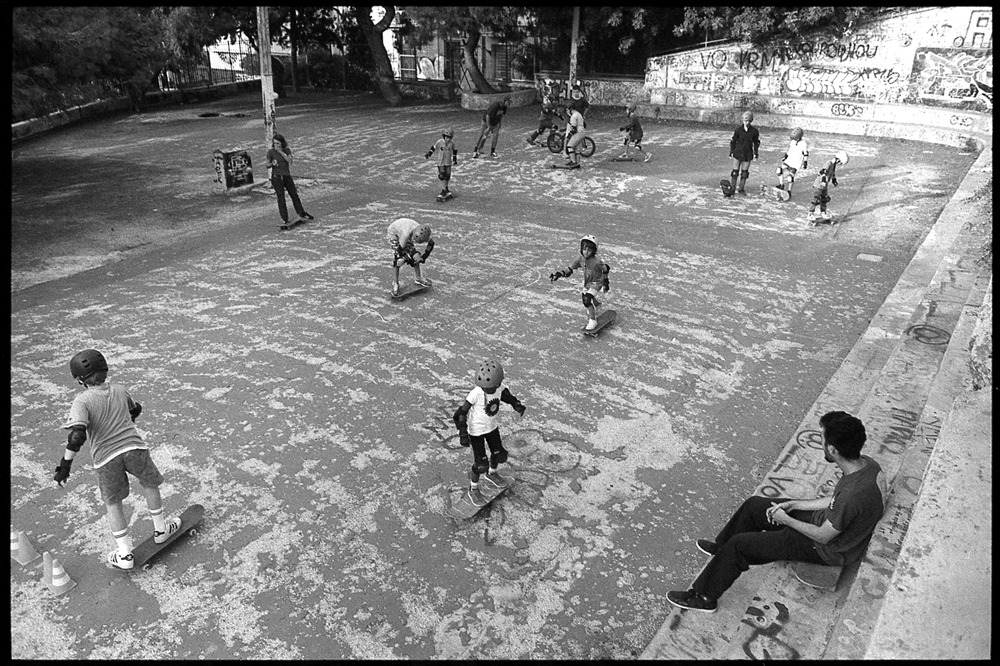

FMS team member Joe helping out at a Monday session at Fifth School, Athens.

“Back in 2019, when people could travel without worrying about spreading the plague, Owen Godbert and I spent the month of October volunteering with Free Movement Skateboarding in Athens. Free Movement (FMS) is a non-profit that runs skate sessions for local and refugee children, promoting equality, integration, and wellbeing. Owen and I were encouraged to volunteer by our good friend and FMS Programs Director Amber Edmondson, who we met when we were all volunteering in Palestine and who ended up being our host for the month.

I had been to Athens once before, but not really; three passive days of tourist attractions and Greek salads had done nothing to prepare me for the reality of Greece’s refugee and economic crises. I had of course seen the 2015 news stories on Syrian refugees crossing the Mediterannean, but in the following years the coverage had slowed, as if the crisis was over. It was only through spending a month in the city under Amber’s tutelage, and learning firsthand about the lives of the kids that came to our sessions, that I began to understand how far that was from the truth.”

Story by: Max Harrison-Caldwell

Photos and captions by: Owen Godbert

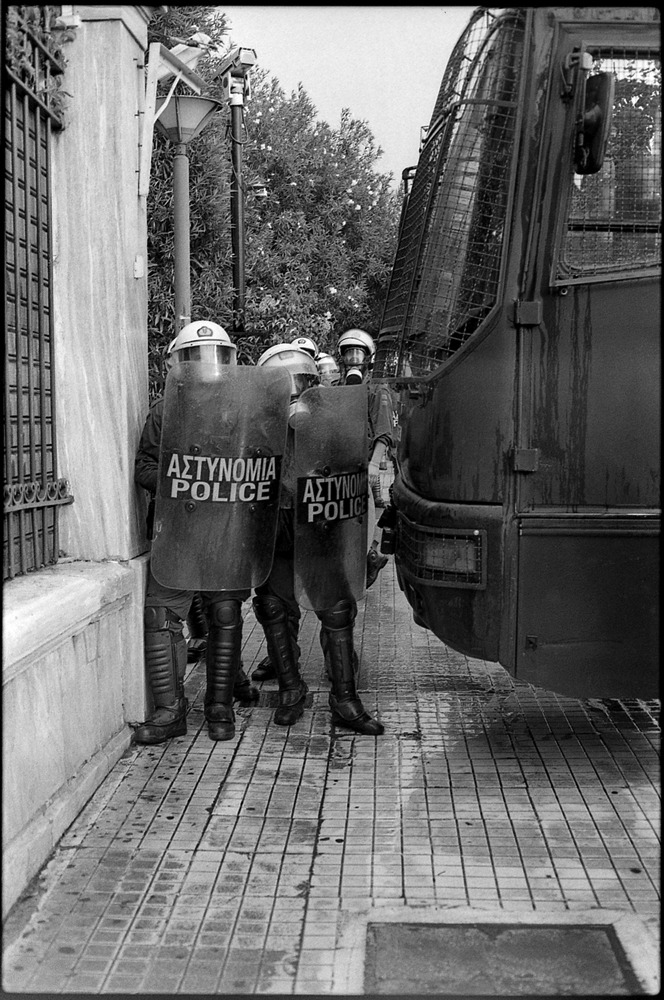

Riot police outside the parliament, Athens.

It was bizarre, the first time we skated to the Fifth School session, to see riot police on Kallidromiou Street. We were carrying our boards up a hill in a stylish, quiet neighborhood, admiring the thrift stores and record shops. The afternoon sun beat down on our backs and we hastened our steps so as not to be late for our first session at the abandoned-school-turned-squat. Suddenly, as we approached the top of the hill, a group of white helmets appeared, then riot shields below them, then black plastic shin guards and heavy black boots. Eight or nine riot cops were spread across the sidewalk ahead of us, smoking and cracking jokes, their attitudes seemingly at odds with the tear gas grenades hanging from their belts. They gave us a curious look as they parted to let us pass.

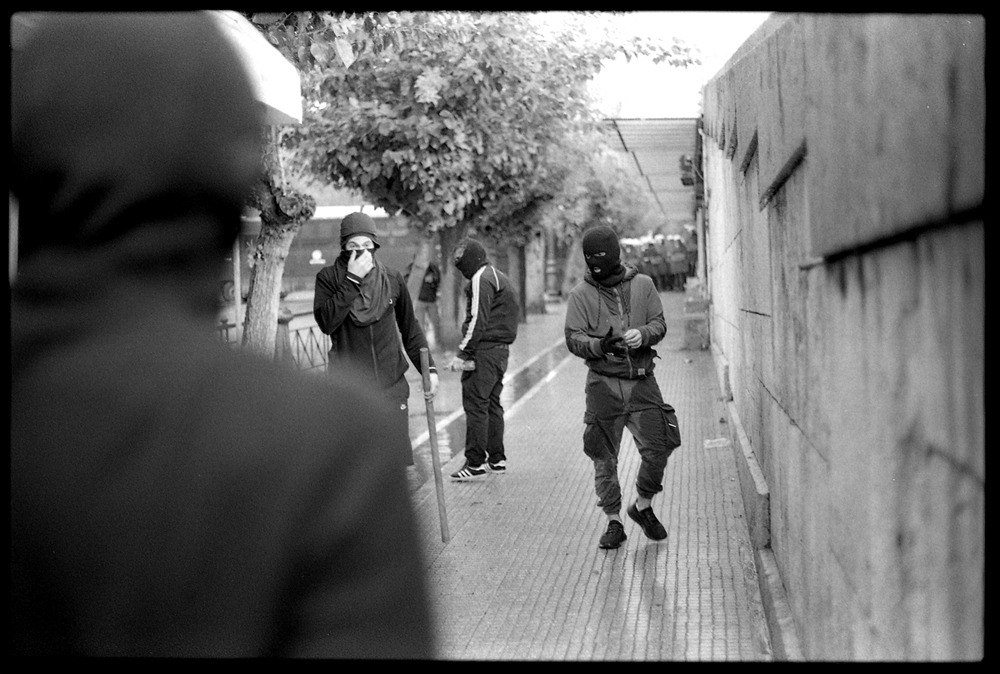

Protesters demonstrating against the abolition of the university sanctuary law, Athens.

Exarcheia, Fifth School’s anarchist neighborhood, used to be essentially self-governing. Squats went undisturbed and the police only crossed into the neighborhood when clashes erupted. Law enforcement officers were banned from the area’s university campuses by the academic sanctuary law, passed in response to the murder of 23 students by the Greek army in 1973. That all ended when the center-right New Democracy party repealed the law in August, a mere month after winning the national election. Now riot squads dotted Exarcheia’s corners, its ancient buildings ominously distorted through their plexiglass shields as they smoked, and chatted, and waited for the next clash with molotov-wielding protestors.

The increased police presence in Exarcheia has gone hand-in-hand with the forceful eviction of local squats, including Fifth School, which was shut down the month before we arrived. Many of these squats were schools that the Greek government abandoned after the economic collapse in 2008. The night after they evicted Fifth School’s 143 refugee residents, Athens police bricked up the entrance to prevent them from returning. Now the building stands empty and useless as its former occupants try to adapt to life in the Corinth camp, where each tent houses 14 families. Twice a week the Free Movement car (the van was out of commission at the time) would park in front of Fifth School’s bricked-up door for our sessions on the adjacent basketball court. A nearby electrical box, decorated with hearts and smiley faces, read “Wellcome to School 5. Have an amazing day.” Local kids at the sessions would sometimes ask us what had happened to their friends who had lived there, and would they ever come back? We’d tell them “maybe one day,” but the truth was that we had no idea.

Fifth School, Exarcheia, Athens.

Some migrants, aware of the hellish conditions in camps like Corinth, choose to take their chances living outdoors. The combination of Greece’s economic and refugee crises has left thousands, both native Greeks and refugees, on the streets. In 2015, the Greek government estimated that 20,000 of Athens’s 660,000 residents were homeless. The next year, a study by KYADA (the City of Athens Homeless Shelter) found that over 70% of these people reported becoming homeless in the previous five years, and that half reported losing their homes after losing their jobs. At the time, Greece had the highest poverty rate in the European Union.

We saw the effects of these crises every day. On the way to La Traac Skate Cafe, we rode down streets lined on both sides with the homeless, tucked into entryways or sitting on the curb shooting up. Locals would walk on the road without a glance at the desperation on either side. But though the drug use was most explicit in Metaxourgeio, there was hardly an alley or avenue in the city without a kneeling beggar, a pair of children digging in garbage bins, or a dirty duvet laid out on a doorstep. Many nights on Patision, one of the busiest streets in Athens, we saw a man sitting on the sidewalk, smoking crack with a blowtorch while pedestrians walked around him. Unkempt old men slept on wooden benches in every park. Smooth jazz from the upscale cafés of Fokionos Negri spilled out onto the boulevard where homeless families foraged for food.

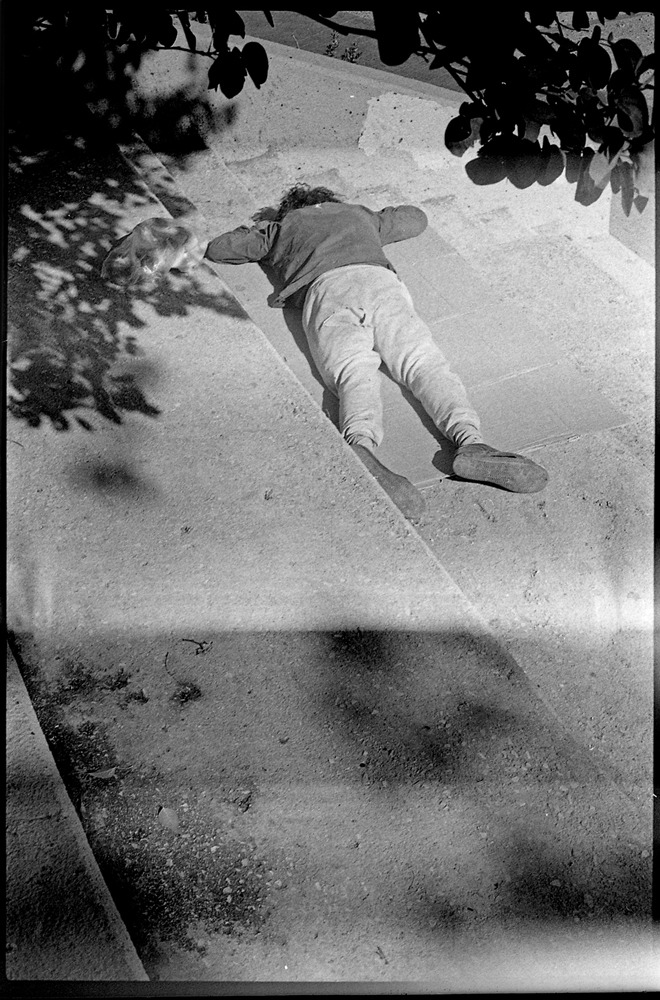

Athens city centre.

This is the city that birthed Free Movement Skateboarding. Before the coronavirus outbreak, the NGO was hosting eight sessions each week: two at Eleonas camp in central Athens, two at Schistou camp in a suburb outside the city, two at Fifth School, and two at La Traac. (After a three-month hiatus, some sessions resumed last week.) Sessions in the camps and at La Traac are closed, but the Monday session at Fifth School is open to the public. Here local and refugee kids skate together, teach each other bits of their native languages, and share a laugh when someone falls off their board.

Metaxourgeio, Athens.

FMS policy prohibits documenting the sessions in the camps, and even in the sessions at La Traac and Fifth School we aimed not to include any faces in our photos. It had happened that a child, photographed at the refugee camp where they lived, had been denied asylum in another country because there was a photo of them playing football online. The asylum board had decided this was evidence that the child was living a happy and safe life in Greece, and did not need refuge elsewhere.

Photography workshop, La Traac, Athens.

As Free Movement co-founder Will Ascott pointed out on Instagram, this is not the case, and weekly skateboarding sessions do little to address the horrors of life in a refugee camp.

“A dear pal of mine reminded me today of the risks of showing the camps as so joyous, especially when in the age of Coronavirus things are getting a lot worse very quickly for our dear friends there,” Ascott wrote. “How can you follow self isolation guidelines when seven families live in a container made for two? Coupled with malnutrition and chronic under-provision of healthcare, there are so many at-risk people in a small space.”

Max, Glyfada DIY, Athens.

Even before the Coronavirus pandemic, camps were overcrowded and underserviced. Pulling up to Eleonas Camp twice each week, we would drive past the rows of tents outside the gate where families who had been denied entry made their homes. One evening, as we left after sundown, we saw a young mother sitting outside her tent, trying to soothe her wailing infant, and gazing wearily at the barbed wire atop the camp’s cement wall.

Max, Glyfada DIY, Athens.

The camps are transient places. People generally don’t know how long they’ll be stuck in them, or where they might be sent afterwards. We met four-year-old children who had been born in the camps and lived their whole lives there, but we also met those who were sure that Greece was just a pit stop on the way to a better life. I met a 20-year-old in the Schistou camp who said that, though he’d been there for a year, he had not learned Greek and did not plan to. Instead, he was teaching himself English in preparation for a future in the UK. He spoke calmly of his life in Afghanistan, his older brother with whom he had lost contact, and his ambitions to live in the countryside. His plans seemed incongruous with his situation (unless he risked using a people smuggler, he would be in Greece for at least five years), but given the uncertainty of his day-to-day life, maybe he needed a dream like that to keep him sane.

Scrappy, Amber & Max on the beach. The whole five weeks or so I was in Athens was spent with these three. It felt like a proper little family!

Hiring a smuggler to transport refugees across state borders is incredibly dangerous. Often, most of a person’s friends and family members won’t know that they plan to leave until they’ve already gone. One day at Eleonas one of our regular skaters, a nine-year-old girl, didn’t show up to the session. Amber went to find her sister and ask where she was.

“She’s gone,” her sister said. “To Germany.”

“To Germany? I didn’t even get a chance to say bye.”

“I know,” said the sister. “Neither did I.”

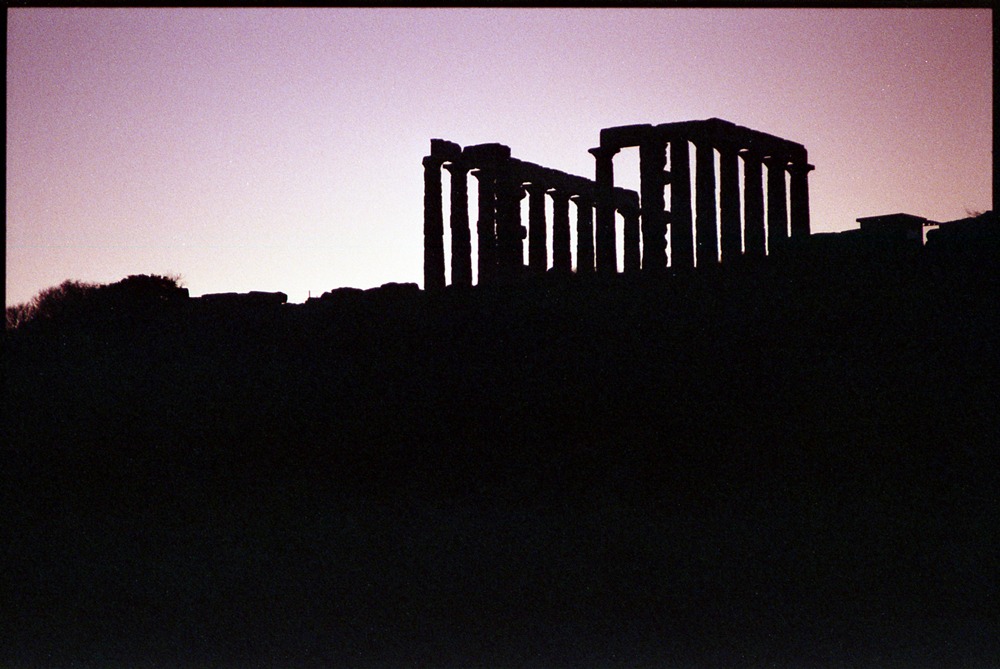

Temple of Poseidon, Sounion.

Skateboarding cannot provide shelter or healthcare or clothing or freedom of movement between countries. It cannot expedite the asylum application process. It cannot protect refugees from violent nationalists. What it can provide is a diversion for bored kids, and an endless set of skills to work on. Each time we pulled into a camp, cries of “Skateboard!” rang out in the stillness and children ran to get their friends. It could be a struggle to get the pads on their tiny, wriggling limbs while they jumped in excitement, eager to secure their favorite boards, and even more of a struggle to keep the smaller ones from running into each other once they got rolling, but to see a kid persevere through a half hour of falling and learn something new made it all worth it.

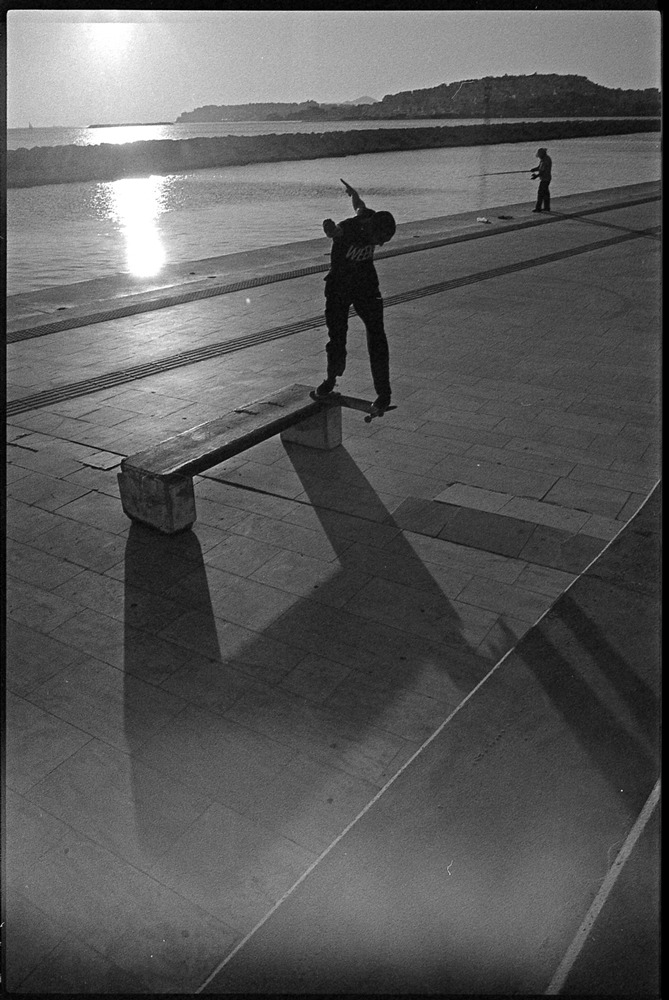

Max, fakie front nose, Piraeus.

Apart from its value as a diversion, skating teaches kids the rewards of hard work and the value of caring for one another. It can provide a network for those who make it out of Athens — one former FMS skater is now living in Belgium, where she has been welcomed into the skate community — and foster trusting relationships with the FMS staff, who are there every week to help kids up when they fall. Skateboarding can also heal trauma in the brain and aid cognitive development. Not only does it provide an opportunity for kids to be kids, playing actively and creatively, but it can also better prepare them for adulthood.

Max, backtail, Piraeus.

One Saturday after a busy week of sessions, Owen and I went to the city’s most famous skate spot, a pair of icy-slick harborside benches in Piraeus. The sun was unrelenting and the cement esplanade offered no shade, so after finally getting our tricks we leapt into the harbor. Feeling my sweat mingle with the salty waters of the Saronic Gulf, I reflected on what a privilege it was to spend languid afternoons skating street and bathing in the sea. The only kids in Schistou who had seen Greek beaches had washed up on them, terrified, in boats and rafts. Their Greece was not made of shimmering sands but of cement, razor wire, and shipping containers. It was filled with riot police and violent nationalists — a far cry from the holiday paradise we were enjoying. And yet, we were able to share a fleeting feeling of freedom with them every week when we skated. It’s not pulling people out of the sea, it’s not distributing medicine and diapers, and it seems insignificant in the larger struggle for human rights, but skateboarding spreads joy. While we continue to fight so that Athens’s displaced children can move freely, Free Movement continues to meet them where they are and enrich their lives. And any skater can help out.

Donate to and volunteer with Free Movement Skateboarding.

Special thanks to Amber Edmondson.

Photos and Captions by Owen Godbert (below)

A protester outside the parliament building in the centre of Athens demonstrating against the abolition of the so-called university asylum law, which banned police from entering university campuses. Although I had planned to attend some of the protests, I found myself at this one by accident. Around half an hour before this, I was walking around the eerily quiet and almost sterile cleanliness of the nearby Museum of Cycladic Art. I was blissfully unaware that I would soon be scrambling around on the wet tarmac outside, having slipped running from a bombardment of teargas grenades. The gas caused uncontrollable tears and a stinging in my eyes that made it difficult to see through my camera’s viewfinder. It also proved to be effective, at least temporarily, in disorientating and breaking up the crowd. The demonstration continued however, making its way through the city to Exarcheia, followed by a parade of heavily armed riot police.

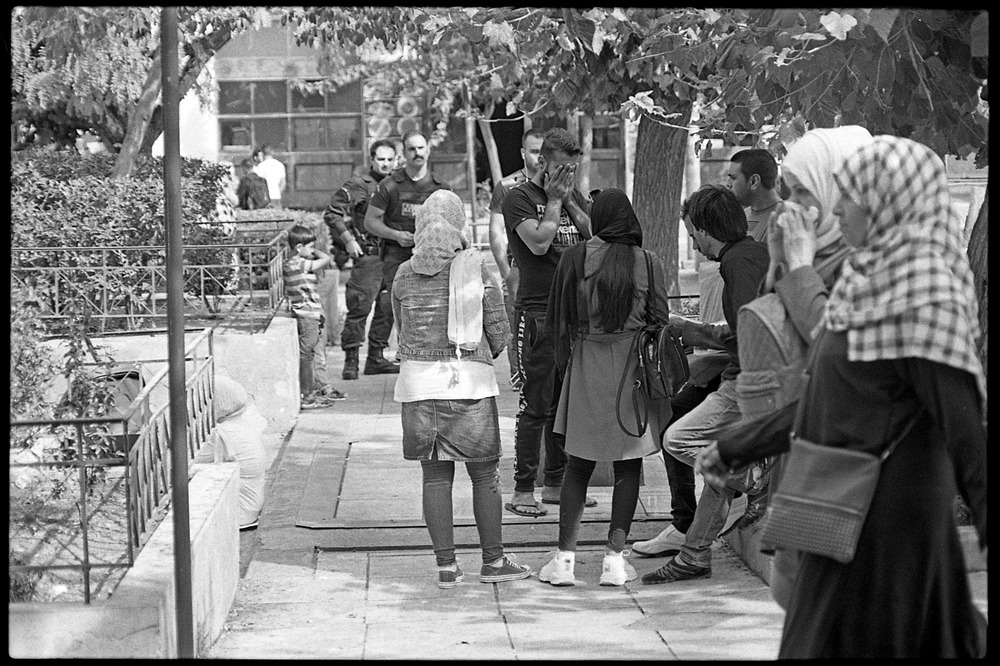

Victoria Square, Athens. As with many of the photographs in this article, this one wasn’t nice to take. Most of what I can say about it is speculative, but what I can say for sure is that this is far from an uncommon sight in Athens. In recent years, Victoria Square has become more than simply a place to drink coffee in the morning sun and buy freshly baked bread. It has also been the home of many refugees and the epicentre of some of the darkest realities of the refugee crisis, including child prostitution. In 2016, two Pakistani men hanged themselves from a tree there. Although I never witnessed such tragedies, there were people in clearly desperate situations whenever I walked through. Despite this, the square remains a vibrant, bustling plaza lined with busy cafes and bars. The disparity here is not unique. In Athens, both the tourism and the local cafe culture, set amid the city’s beautiful architecture, exist in stark contrast to the cruelty and suffering present throughout the city. The abandonment and neglect of both humans and buildings is clear to see. Foreign migrants and asylum seekers in Athens regularly face police checks to examine their documents and to verify their legal status. Even when all of a migrant’s documents are in order, police will still sometimes confiscate those documents, which then become lost in the impenetrable bureaucracy. The individual, now paperless, is vulnerable to harassment and deportation when the police inevitably stop them again.

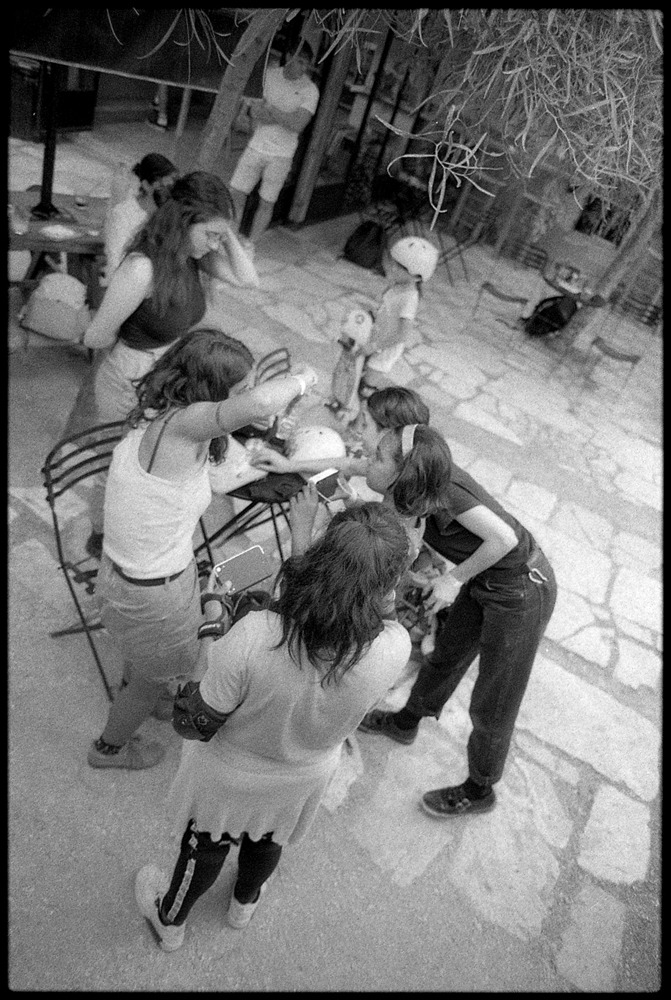

Inclusivity and integration are of huge importance to Free Movement Skateboarding. However, as access to the camps is restricted, many of the sessions they run can only be attended by the people living in those camps. This isn’t the case for the sessions here. A neglected basketball court on the edge of a wooded residential park provides the near-perfect place to run two weekly sessions. These are open to anyone and we met children of many different nationalities and backgrounds. The atmosphere was quite relaxed and there was a real sense of community as some kids returned each week and helped others who had come for the first time. Although I felt this air of positivity most of the time, there had been an aggressive upheaval only the month prior with the eviction of the Fifth School squat. Many of the friendships forged at the sessions here, between Fifth School residents and locals alike, were cut brutally short.

La Traac is a café bar that has a large outdoor area with a skate ramp tucked away at the back. The staff kindly allow FMS to host two afternoon sessions there every week before they open up for the evening. Like the Fifth School sessions, anyone is welcome to attend these, but the main function is to provide children from Eleonas camp a chance for a weekly excursion outside the confines of the camp. It’s here where some of FMS’s extracurricular activities take place. They host a women’s program as well as other creative workshops. While I was there, we held a photography workshop using some instant printing cameras generously donated by a previous volunteer. One of the girls in particular enjoyed the class so much and showed such enthusiasm for photography that I lent her my point and shoot camera and a roll of film to use over the weekend. I’ve been told that she is still a keen photographer and that there was even talk of her photographs being featured in an exhibition before all the inevitable disruption caused by the coronavirus.

Although he never said as much, this guy definitely considered himself the king of the beach that we camped on in Agistri. Having first approached us offering his ouzo in exchange for a cigarette, he then felt comfortable enough to come over and help himself as we were chopping vegetables for tea, much to our amusement. He’d lived on the beach here for months and he appeared to welcome each new visitor who arrived. Later that evening he joined us as we lay on the sand drinking a few beers. He’d put on some clothes by this point, but still not many. As Felix and Max drifted off to sleep, the beach king (unfortunately I don’t ever recall getting his name) and I went for a long walk all around the island, barefoot, with his huge bottle of ouzo. I do remember having great conversations with him, but I can’t seem to remember what any of them were about! After a few hours walking and talking together, we returned to the beach and I went to sleep on the sand. I had accidentally carried two heavy tents to the island with me, rather than one tent and a sleeping bag, only to end up not using either of them!

Big thanks to Max Harrison-Caldwell and Owen Godbert for taking their time to shed light on this for us. You can support Free Movement Skateboarding here.